Heads up, guys: I’m going to use some offensive language in this post. Partly because it’s about offensive language. You can be offended and walk away, or you can read the post and then decide what you think. I’d prefer the latter, but I understand the former.

“Hey, read this thing!” I say, handing my phone to a friend. “It’s hilarious. Oh–but it has some language.”

That’s a regular occurrence for me. I recently shared a funny picture to my baby brother’s Facebook wall, only to delete it seconds later because I realised it had the word “shit” in it, and probably my parents would not be thrilled with me sharing that sort of language to my impressionable teenage brother, no matter how funny the comic was.

And, guys, that bothers me.

It was this comic, by the way, and I’m still snickering over it. If you don’t think this is hilarious, we have a serious problem.

Not the protective parent thing; my parents are basically the best thing ever. But the whole language thing in general. Permit me to wax eloquent.

A word is a funny thing. A simple combination of letters and sounds can evoke some crazy psychological responses. If I say “pink elephants,” one person might envision a pink pachyderm, and another might remember the smell of funnelcakes from the fair where a stuffed pink elephant hung over a game booth, and yet another (this is me!) might start humming the Pink Elephants On Parade song from Dumbo.

But, despite all these associations, the letters and sounds themselves are just that: letters and sounds. They only have the meaning we give them.

Now let’s talk about a different word. Let’s take “bitch.” If I say “bitch,” one person might envision a dog, another might think of a crazy ex-girlfriend, and yet another might imagine a two-year-old whining about something. And some people will immediately forgo any association except shock at my language.

But still, the letters and sounds themselves are just that: letters and sounds. They only have the meaning we give them.

We’ve all seen those fun “which region is your dialect” quizzes that ask you whether you call it “pop” or “soda” or “coke.” So what’s the difference whether I call it “complaining” or “whinging” or “bitching”? The difference is, some people will be highly offended at one–maybe even to the point of not hearing my meaning, so hung up on that one particular word that they miss the rest. Words that kids today get their mouths washed with soap for saying were common usage a hundred years ago (back to our example of “bitch”–and here is a fun article about how this happens). Words that we say without compunction in one part of the world are highly offensive in others (“fanny” might be polite in the US, but please don’t say it in parts of the UK).

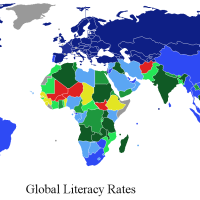

And those regional dialect quizzes are definitely important, especially if you, like me, aren’t entirely sure where your vocabulary came from…

And guys, I can say “bitch” with a perfectly good attitude and “meany-face” with murder on my mind, and many people will excuse “meany-face” and judge “bitch.”

In his book On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft, Stephen King expresses a dichotomy of opinions: on the one hand, swearing is, “the language of the ignorant and the verbally challenged;” on the other, “It’s important to tell the truth; so much depends on it.” And as he sees it, sometimes the truth involves rude language. I’m not here to tell you that you should brush up on terms that would shock your grandmother. I am, however, suggesting that you don’t shut off a whole world of thought because one word offends you.

Offensive language doesn’t offend me. I choose not to use it out of respect for people who might be offended, desire to use more creative language, and a sort of selfish desire not to talk like everyone around me (I’m probably the only one at my university who still occasionally says, Oh my stars and garters!, and I like it that way)–but I don’t cringe when I hear it in films or read it online. And you know what? I think I’d miss a lot if I did. Some of the most impactful things I’ve ever read were posted on Tumblr, replete with sketchy punctuation, no capitalisation (except for those occasional all-caps rants), and more instances of “fuck” than I knew you could cram in one sentence. These are the kind of things I consider sharing with friends and then don’t, because I can already imagine the scene:

Friend: “That had a lot of f-words in it. Are you sure you sent me the right link?”

Me: “Right, yeah, I know, but the content. Didn’t you think that was super funny/deep/though-provoking/some other worthwhile quality?”

Friend: “…you know, I just don’t think you need to use bad language to express yourself. It shows ignorance/lack of class/bad upbringing/some other negative quality.”

Me: “But the content. Did you get the content?!”

We see a four-letter word, some sort of guilt starts tickling under our ribs, and there’s a whole world we don’t see because we choose not to look. Because it might not be pretty and clean. See, we who try not to swear, we miss out. We miss great jokes because whoever told them used words we didn’t like. We miss deep thoughts because someone expressed them with language our mothers told us not to use. We miss people’s hearts because they aren’t as tidy and conventional as we’d like.

Guys, we miss hearing people’s stories.

Here is a thing that supposedly Oscar Wilde said but that I can’t find anywhere in the original play, and which I therefore think came solely from the movie. No matter where it came from, it’s beautiful and important.

Christians have a reputation of being judgmental, straight-laced, and hypocritical. And for some reason this surprises us.

I’m not saying we should all adopt sailor-grade colourful language, but maybe we should consider the fact that our petty war on four-letter words is preventing us from fighting for people’s hearts. And people matter more than my righteous indignation any day. If we can’t hear someone’s story beyond the language they use to tell it, the whole “judgmental, straight-laced, and hypocritical” label isn’t a misunderstanding–it’s a truth. A truth that, ironically, we can’t hear because it’s probably expressed with a few offensive terms. People don’t want your sermons or your “Jesus can fix you” platitudes. They want you to care. To hear their stories, to love them where they are, to say, “You matter, right now, right here.”

Guys, can we stop being offended long enough to listen?